Helga Goetze

1922 – 2008

Helga Goetze (* 1922 Magdeburg, Germany, † 2008 Winsen, Germany), also known as Helga Sophia, was a German artist, writer and political activist, who lived and worked in Hamburg and Berlin.

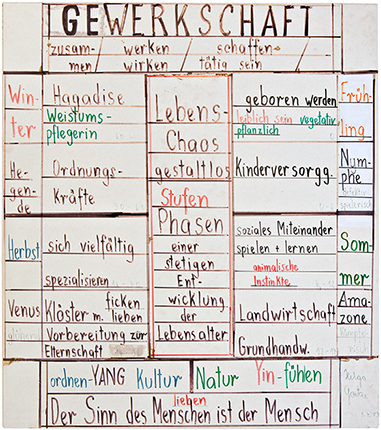

In 1972 she founded the Institute for Sex Information and published her first poetry collection Hausfrau der Nation oder Deutschlands Supersau (Housewife of the Nation or Germany’s Super Sow). Later on, Goetze kept close contact with the commune founded by the Vienna performance artist Otto Mühl and was actively associated with the Hamburg cultural centre “Fabrik”. After moving to Berlin in 1978, the artist started to maintain daily protest pickets in favour of women’s sexual liberation in front of the Technical University as well as the Berlin Gedächtniskirche. In Berlin, she also founded the “Geni(t)al University”, a gallery and open museum. Conversations with Rosa von Praunheim inspired her to make the film Rote Liebe (Red Love) in 1982. With the 1982 TV show Neue Nackte, neue Einsichten (New Nudes, New Insights), where she undressed in front of the camera, and several appearances on TV talk shows during the 1990ies, Goetze challanged the public debate around sexuality in the media. In 2000, she founded the association Metropole Mutterstadt e.V. (Metropolis Mother City) with a group of friends and in 2003, Monika A. Wojtyllo made a film about the artist, titled Sticken und Ficken (Embroidery and Fucking), which was shown at several festivals.

Goetze’s works have been presented in the context of various events, readings and exhibitions, including the Museoteatro della Commenda di Prè in Genoa, Italy; the Bratislava Triennial, Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, Slovakia; the Complesso Museale Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, Italy; and the Museum im Lagerhaus, St. Gallen, Switzerland. Since 2007, her embroideries have been part of and are on permanent display at the Collection de L’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland. Since 2014, the artist’s literary estate has been located at the archive of the Frauenforschungs-, Bildungs- und Informationszentrum Berlin (Women’s centre for research, education and information, Berlin).

—

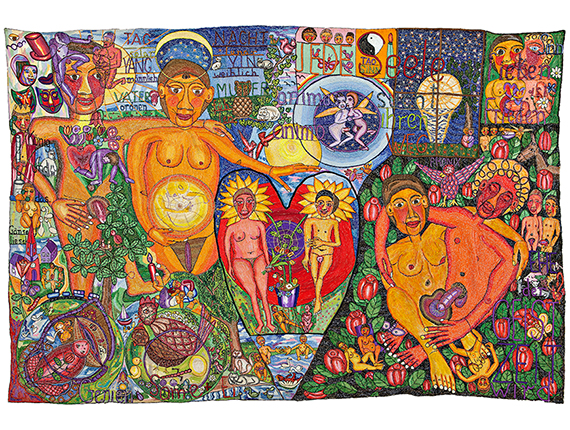

Lines of silver thread run through each being and life form with a soul in Helga Goetze’s epic embroidery, Indianische Astrologie. The landscape is one of spiritual union and interconnection, inhabited by peaceful beings, most of them engaged in one activity – fucking.

For Helga Goetze, “Ficken ist Frieden,” a statement that recurs in her more than 3000 poems, drawings, erotic tapestries, and her activism. Articulated in her prolific work is a form of faith – sex as a pathway into the hidden, obscure, unknowable registers of our being and existence. During her daily one-person protests by the Gedächtniskirche in Berlin, she could have spoken of love, or love making, but Goetze preferred referring to her faith as fucking. A word choice and provocation of a woman in her seventies that was, and is, significant and deliberate.

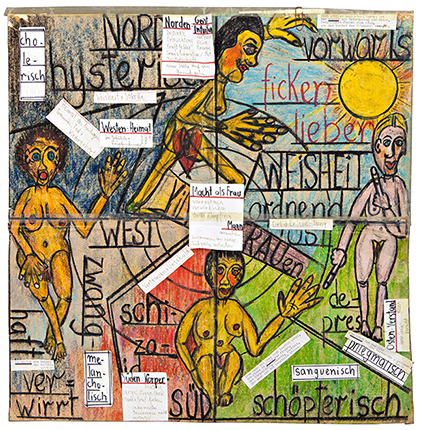

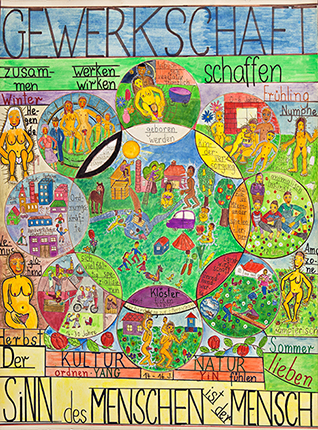

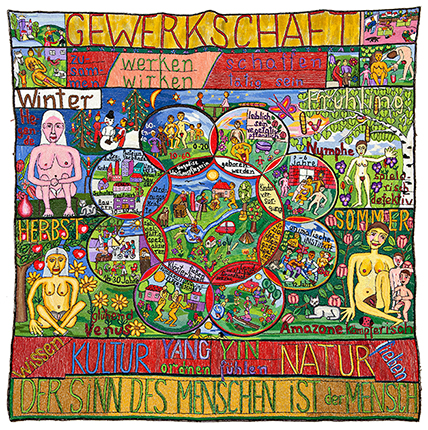

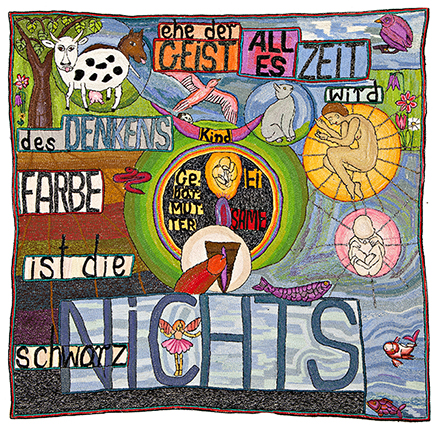

There is a continuous movement in Goetze’s practice between the advocacy of pleasure, and a fascination with the fear or suppression thereof. Her embroideries are large, complex and harmonious compositions of image and text, with bright primary colours. These works are depositories of time – a repetitive and precise labour – sitting at the interface between mind and hand. Goetze used a craft, traditionally associated with female subjection, and pushed its form and expression into radical visions of love, motherhood and co-habitation.

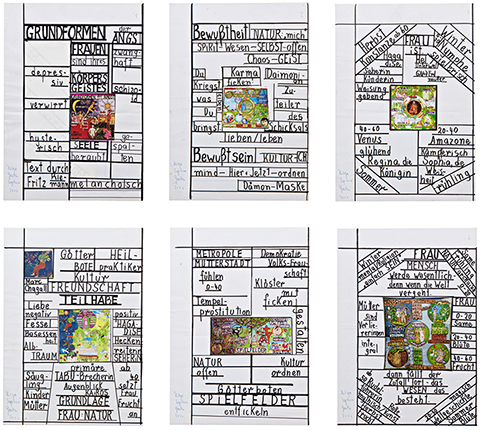

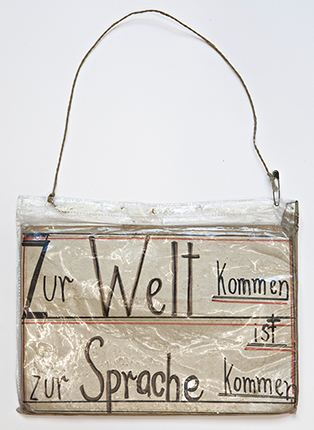

Her poems and text-works oscillate between the search for a profound state of truth – an eloquently formulated spiritual outlook – and a deeply felt critique of patriarchy: “with the contempt of woman begins the end of the world.” Her compositions of text on board reveal a system of thought, held together by interconnected lines. For Goetze, writing was a core way in which her systemic-intuitive thinking crystallised itself, and was carried forth – “Coming into the world means coming into language.”1

Goetze married young, and spent the first part of her adult life as a housewife and mother. In her mid 40s she experienced a powerful sexual revelation, and lived for a number of years in free love communes in Hamburg and Berlin, before founding the ‘Genital University’ in her home. The force or “Kraft” that propelled her work and thinking was defined against ideals of control and order – of sanitized, and in Goetze’s words, “neurotic ideals of the nuclear family.”22 Perversion, in her work, is rooted in the structural ‘perversions’ of normative desires and its associated controls. A recurring symbol of dominance and infantilisation in her imagery is the pointing index finger. One of them is raised and belongs to a man, her father. “You do not see and you do not touch,” written next to it. And on the other side the mother with the words: “That stinks.”3

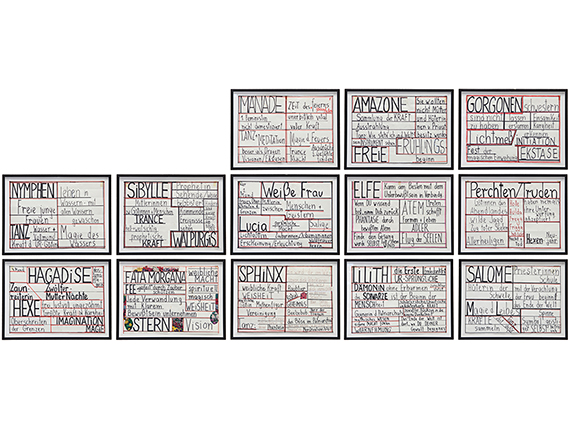

To speak of love, pleasure and joy, is in Goetze’s work both an affirmation of a way of being together and a deliberate act of subversion. Deep-seated fears of female sexuality, and in particular that of an older woman, were core threads of her practice, ones that she explored with and through her own mythological lexicon. There is a cyclical sense of time in Goetze’s work and her compositions recurrently couple organic temporalities with female experience. As the figures move from spring to winter, an intellectual, embodied and sensual process of change is represented, without one stage being privileged, or another reduced. In Die Göttinen, hand-drawn text and collage elements are structured around a series of mythological female beings – their lessons are distillations of Goetze’s views on imagination, energy and the sacred, alongside critiques of private possession and spiritual boorishness. Part of the implication here, as elsewhere in Goetze’s work, is that we already know, or at least knew how to be in the world; that there are deep connections and intuitions that have been silenced, and at times violently severed. Her outlook, however, was also cut through by a humour and defiance that destabilised any potential sanctity of vision. There is a significant impurity, and distrust of morality that fed into her attitude, and language. She often referred to herself as a “housewife”, “a hole”, “a sow” – as much a strategy of provocation and defiance, as a pleasurable undermining of over-simplified and binary division between power and suppression. In Goetze’s lifetime, there was a lack of critical engagement with her practice, and the tendency to diminish, even pathologise, her person and work. An element experienced all the more intensively as Goetze did not remain within the comfort and safety of initiated circles, but decided to speak and take space in distinctively public-facing platforms. As such she was familiar with reactions of fear of the unknown or the uncontrollable, reactions which Goetze saw and at times confronted with a combination of spite and sardonic wit:

Without ears, this sow

Do you really call such a thing a woman?

And this is me.4

When a body loves, it shows an admirable frailty, a state which fascinated Goetze. It is a strand rooted in, but extending beyond the erotic – hers was an anti-patriarchal, anti-capitalist and ecologically permeated way of seeing, with circles of concern radiating outwards. We know that there is more than one reality, multiplicities or “thresholds” sensed or experienced, in spite of dominant ideology’s insistence on the singular narrative. Part of the confrontation of Goetze’s ‘vision work’, a confrontation it purposefully courts, is a deep-running insistence on staying put with, and enduring a radical unity of parts. “It does not have to be right – but sometimes it’s mysterious how everything is connected.”5

Fatima Hellberg

- Quote from Helga Goetze, Salome from the series Die Göttinnen, undated, mixed media on paper, 41 x 29,5cm.

- From Helga Goetze, “Ficken für den Frieden” 1993, interview, Published on ‘Youtube’ March 30, 2017

- Leila Dregger, ‘Helga Sophia Goetze – Die Frau wird zur glühenden Venus’, from ‘Die weibliche Stimme’, undated.

- Excerpt from Helga Goetze’s poem, ‘Sperma, Piss und Menschenkot’, 1973, URL, ibid.

- Helga Goetze, ‘Philosophie und Religion’ quoted (undated) on ‘Helga Sophia Goetze’